Abstract

Background

Despite the evidence in support of the use of buprenorphine in the treatment of OUD and increasing ability of emergency medicine (EM) clinicians to prescribe it, emergency department (ED)-initiated buprenorphine is uncommon. Many EM clinicians lack training on how to manage acute opioid withdrawal or initiate treatment with buprenorphine. We developed a brief buprenorphine training program and assessed the impact of the training on subsequent buprenorphine initiation and knowledge retention.

Methods

We conducted a pilot randomized control trial enrolling EM clinicians to receive either a 30-min didactic intervention about buprenorphine (standard arm) or the didactic plus weekly messaging and a monetary inducement to administer and report buprenorphine use (enhanced arm). All participants were incentivized to complete baseline, immediate post-didactic, and 90-day knowledge and attitude assessment surveys. Our objective was to achieve first time ED buprenorphine prescribing events in clinicians who had not previously prescribed buprenorphine in the ED and to improve EM-clinician knowledge and perceptions about ED-initiated buprenorphine. We also assessed whether the incentives and reminder messaging in the enhanced arm led to more clinicians administering buprenorphine than those in the standard arm following the training; we measured changes in knowledge of and attitudes toward ED-initiated buprenorphine.

Results

Of 104 EM clinicians enrolled, 51 were randomized to the standard arm and 53 to the enhanced arm. Clinical knowledge about buprenorphine improved for all clinicians immediately after the didactic intervention (difference 19.4%, 95% CI 14.4% to 24.5%). In the 90 days following the intervention, one-third (33%) of all participants reported administering buprenorphine for the first time. Clinicians administered buprenorphine more frequently in the enhanced arm compared to the standard arm (40% vs. 26.3%, p = 0.319), but the difference was not statistically significant. The post-session knowledge improvement was not sustained at 90 days in the enhanced (difference 9.6%, 95% CI − 0.37% to 19.5%) or in the standard arm (difference 3.7%, 95% CI − 5.8% to 13.2%). All the participants reported an increased ability to recognize patients with opioid withdrawal at 90 days (enhanced arm difference .55, 95% CI .01–1.09, standard arm difference .85 95% CI .34–1.37).

Conclusions

A brief educational intervention targeting EM clinicians can be utilized to achieve first-time prescribing and improve knowledge around buprenorphine and opioid withdrawal. The use of weekly messaging and gain-framed incentivization conferred no additional benefit to the educational intervention alone. In order to further expand evidence-based ED treatment of OUD, focused initiatives that improve clinician competence with buprenorphine should be explored.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03821103.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Emergency departments (EDs) are uniquely positioned to expand access to treatment for patients with opioid use disorder (OUD). Overdose rates in recent years have escalated and much of this is attributed to the increase of fentanyl in the drug supply [1, 2]. A recent analysis of 25 EDs across multiple states found that opioid overdose visit rates increased by 28.5% in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to 2018–2019 [3]. These patients are most vulnerable, experiencing a 5.5% risk of death 1 year following an ED visit for non-fatal opioid overdose, suggesting EM clinicians should prioritize treatment engagement [4]. Treatment of OUD with buprenorphine decreases both withdrawal symptoms and cravings for opioids and can be safely and effectively initiated from the ED [5,6,7]. Patients who receive buprenorphine are less likely to suffer a non-fatal or fatal overdose, use illicit opioids, develop Hepatitis C or HIV, suffer other infectious complications, or have contacts with the criminal justice system [8, 9].

However, access to buprenorphine is limited. At the time of our intervention, in order to prescribe buprenorphine, clinicians were required to complete an 8-h training course and receive a “DATA-waived” registration to their U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) license (“X-waiver”) through the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Buprenorphine prescribing has been low, with over half of waivered physicians not prescribing to capacity or not prescribing at all [10]. One study of providers in Washington demonstrated that in the 7 months following the full X waiver training, only 28% had ever prescribed buprenorphine. This gap between training and practice exacerbates the problem of insufficient treatment access. Additionally, negative attitudes about buprenorphine from providers are common and even those who report positive attitudes are unlikely to prescribe, with a lack of clinical confidence or institutional support cited as barriers [11,12,13]. Incentives have been shown to be effective at augmenting the implementation of ED buprenorphine programs, both in the number of X-waivered EM clinicians and the number of ED-buprenorphine prescriptions [14]. The ED patients with OUD who receive buprenorphine have twice the rate of treatment engagement at 30 days compared to those who receive discharge referral alone, suggesting a significant opportunity for EM clinicians to increase patient opportunities for treatment [15].

Studies have found that lack of training and experience treating OUD with buprenorphine is a major barrier to ED-initiated buprenorphine among EM-clinicians [16, 17]. One study reported that only 44% of EM clinicians felt they were prepared to discuss addiction treatment while another found that among clinicians who reported lack of training as a barrier, 64% reported that having training would increase their likelihood of initiating buprenorphine [13, 18]. In a multi-state survey in 2020, Zuckerman et al. found that among non-waivered ED physicians only 34% reported feeling comfortable initiating buprenorphine treatment and nearly half (47%) felt that it was not their job [18]. While buprenorphine administration was shown to have increased in EDs between 2002 and 2017, the prevalence of buprenorphine use in the ED remains low [19]. Myths and confusion about regulations create further barriers to ED buprenorphine administration. While the Biden administration removed the requirement of federally specified training in order to be permitted to prescribe buprenorphine to less than 30 patients at any one time, physicians must still apply for a waiver through the DEA. Additionally, buprenorphine may be administered in the ED by a non-waivered clinician through “the 72-h rule” (Title 21, Code of Federal Regulations, Part 1306.07(b)), which allows all clinicians “to administer narcotic drugs for the purpose of relieving acute withdrawal symptoms when necessary while arrangements are being made for referral to treatment” [20, 21]. Thus, regardless of their waiver status, the ED clinicians are permitted to administer buprenorphine to their patients to treat opioid withdrawal.

To target the barriers preventing EM clinicians from administering buprenorphine to eligible patients (patients with OUD who exhibit symptoms of at least mild opioid withdrawal), we piloted a randomized control trial (RCT) testing the impact of behavioral incentives to enhance a didactic intervention to inform EM clinicians about the pharmacologic characteristics of buprenorphine, the physiological considerations of opioid withdrawal, the regulations around ED-administration of buprenorphine, and the framework of a “warm hand-off.” Our objective was to achieve first-time ED buprenorphine prescribing events in clinicians who had not previously prescribed buprenorphine in the ED as well as to improve EM-clinician knowledge and perceptions on ED-initiated buprenorphine. We assessed baseline knowledge and attitudes and evaluated the effect of the educational intervention immediately after the session and again at 90 days. We hypothesized that a brief educational intervention would increase knowledge and improve attitudes, translating into practice change (the outcome of administering buprenorphine to a patient for the first time) among all EM clinicians. Furthermore, we hypothesized that utilization of additional behavioral-economics-framed nudges and weekly texts with buprenorphine-evidence statements would contribute to retention of knowledge and favorable attitudes and enhance the outcome of change in practice (buprenorphine administration) compared to educational training alone. Notably, this study was designed prior to the recognition of the changed drug supply from heroin to fentanyl and any subsequent considerations of buprenorphine use in patients using fentanyl.

Methods

Participants

Emergency medicine (EM) clinicians (residents, advanced practice providers (APPs), fellows, and attendings) practicing in EDs in the Greater Philadelphia area and in attendance of one of the targeted conferences or meetings were eligible to participate in this pilot study. The study was deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania and was pre-registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier: NCT03821103). Participants were recruited at educational or administrative conferences from February 2019 to October 2019. Eligibility was screened through an automated text-based survey. Clinicians were eligible to participate if they answered ‘no’ to the question “Have you ever administered (ordered and/or prescribed) buprenorphine or buprenorphine-naloxone (Suboxone) for a patient with opioid use disorder?” Individuals who were already “X-waivered” were included if they had not yet administered buprenorphine. We only included clinicians who had not yet administered buprenorphine (regardless of their waiver status) because we believed this group of clinicians would most benefit from training on the clinical and operational considerations of treating OUD in the ED, a competence that ED clinicians who administer buprenorphine routinely likely already possess.

Educational Intervention

The training didactic was offered during existing educational conference time or administrative department meetings for EM residents, fellows, attending physicians, and APPs. Attendees were recruited to participate and asked to complete a text-based eligibility screening survey. While we did not record how many total individuals were in attendance at the meetings, 227 individuals texted in response to our prompting to determine if they were eligible to participate. The survey was administered through Mosio (Seattle, WA), a software company specializing in mobile solutions for research. The training consisted of: 1. A baseline survey; 2. An evidence-based didactic and ED case-based review of buprenorphine, and 3. A post-intervention survey. The content was summarized from the DATA 2000 waiver course and included an overview of the opioid crisis, pharmacology of buprenorphine and naloxone, clinical signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal, information on the “72-h rule,” introduction to the concept of a “warm hand-off”, and an interactive clinical case discussion.

All the eligible participants completed a baseline text-based survey prior to the didactic training. Survey questions solicited demographic information (level of training, institution, and X-waivered status) and answers to six multiple-choice queries to assess knowledge of buprenorphine, and three Likert-scale assessments on views towards ED-initiated buprenorphine (Appendix A). All the participants underwent the 30-min didactic training described above and then were prompted to complete a second survey reassessing their knowledge and attitudes immediately after the didactic. The participants were given the second survey approximately 45 min after the first survey. The knowledge assessment questions in both surveys were the same but the order in which they were asked varied. Upon completion of the 2 surveys and didactic training, the subjects were compensated with an electronic code to a $15 gift certificate. For consistency, one author led all of the trainings [22].

Following the training, the participants were randomized into one of two arms using a random number generator: a standard arm and an enhanced arm. The participants were unaware of their randomization and of the other study arm, and had no additional contact with other participants through our study. The subjects in the standard arm received no further communication until 90 days, when they received the final survey. Those in the enhanced arm were notified via text message that they would receive an additional financial incentive ($20), if they texted to report administering their first dose of buprenorphine in the ED. All the participants had been instructed during the didactic that patients must be in at least mild opioid withdrawal (with a COWS score of at least 8) to be clinically eligible for buprenorphine. Additionally, the participants in the enhanced arm were enrolled to receive weekly text messages that included clinical pearls, as well as social norming, stigma-mitigating, and salience highlighting content about opioid use disorder and buprenorphine [23]. At the end of 90 days, both groups received SMS-based surveys on the same initial knowledge and attitude questions as well as additional questions on whether or not they administered buprenorphine during the study period, what influenced their decisions to administer or not administer buprenorphine, their overall rating of the training, and feedback comments. All the participants received an electronic code for a $25 gift certificate for completing this final 90-day survey. The purchase of gift certificates was funded through a grant from the Medical Toxicology Foundation of the American College of Medical Toxicology.

Evaluation

A thorough search of the relevant literature did not reveal any pre-existing instruments that specifically addressed our study question. Therefore, we based our items on expert input as well as previously published substance use attitude questions [24].Knowledge assessments were graded based on percent questions out of six that were answered correctly. Attitude-related responses were based on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 3 = neutral, 5 = strongly agree).

Statistical Analysis

Summary descriptive statistics include frequency and percentage for categorical variables and means ± standard deviation for scores. To assess changes in knowledge and attitudes over the 90-day period between the study arms, analysis of variance in repeated measures was used. To minimize type I error, post hoc pairwise comparisons using Tukey–Kramer tests were performed to examine differences at time points and study arm. Outcomes are reported as mean difference with 95% confidence intervals. A sample size calculation was not performed, as this was a pilot study. To assess reported buprenorphine administration, Fisher’s exact test was used. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The data were approximately normally distributed. All the statistical analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (Version 9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Figures were created in Harvard Graphics 3.0.

Results

A total of 227 EM clinicians were screened for eligibility after they texted in to our platform, and 41% were excluded for having previously administered buprenorphine in the ED, and 8.9% were excluded for not completing the initial survey (Fig. 1). In total, we enrolled 104 participants from 11 hospitals: 51 were randomized to the standard arm and 53 to the enhanced arm. All the hospitals were located in the Greater Philadelphia area and included academic and community emergency departments. The majority of the institutions represented were academic EDs (8/11). Of enrollees, 48.1% (n = 50) were resident physicians, 39.4% (n = 41) were attending physicians, and 12.5% (n = 13) were advanced practice providers. A minority of participants (7.7%) were previously X-waivered but had never ordered buprenorphine in the ED.

Prior to the didactic intervention, baseline knowledge scores were similar in the standard arm (67.7% ± 19.0%) and the enhanced arm (68.4% ± 17.1%). At the end of 90 days, 59% (n = 61) of enrolled participants had completed all three assessments and 72.3% (n = 73) had completed the final survey. Clinical knowledge about buprenorphine improved for all clinicians immediately after the didactic intervention 68.4% vs 87.9%, (difference = 19.%, 95% CI 14.4% to 24.5%), but this was not sustained from baseline at 90 days in the enhanced arm 90-day mean 76.9% (difference 9.6%, 95% CI − 0.37% to 19.59.2%,) or in the standard arm 90 day-mean 73.2%, (difference 3.7%, 95% CI − 5.8% to 13.2%) (Fig. 2).

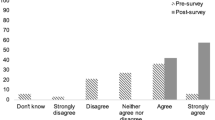

In evaluating perceptions, the participants in both groups expressed an increased ability to recognize patients who are physiologically in withdrawal and would meet the criteria for a dose of buprenorphine (Question 2). This increase was seen immediately after the intervention and sustained at 90 days (enhanced arm, baseline to 90-day difference: 0.55, 95% CI: 0.01–1.09, standard arm baseline to 90-day difference: 0.85 95% CI: 0.34–1.37; Fig. 3). While the participants also demonstrated an increase in favorable attitudes toward medications for patients with OUD (Question 1) and ED-initiated buprenorphine (Question 3), these changes were not statistically significant in either arm (Fig. 3). Additional analyses were performed looking at differences between residents and attending physicians. Advanced practice providers (APPS) were excluded from this analysis due to incomplete data. There was no difference between attending and residents with regard to changes in attitudes from baseline to 90-day surveys (Question 1, difference in change between residents and attendings 0.56, 95% CI − 0.34 to 1.47, Question 2, difference in change between residents and attendings 0.46 95% CI − 0.019 to 1.12, Question 3 difference in change between residents and attendings 0.07 95% CI − 0.60 to 0.73).

In assessing buprenorphine administration, one-third (33%) of all the participants reported administering buprenorphine for the first time during the study period. More participants in the enhanced arm reported administering buprenorphine compared to the standard arm, but this difference was not statistically significant (40% vs. 26.3%, p = 0.319). Among those who reported not administering buprenorphine during the study period, the most common reason provided was not encountering an appropriate patient (75.5%). No participant reported lack of preparation as the reason for not administering buprenorphine. When the participants were asked to rate how likely they were to recommend the initial didactic intervention to a colleague from 0 to 10 (10 being most likely) the mean score overall was 8.3 ± 1.4 and were not statistically different between the enhanced arm and standard arm (8.5 ± 1.5 vs. 8.2 ± 1.8, p = 0.42).

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that a brief educational intervention and text-based survey enrollment and follow-up was feasible and associated with 33% of participants administering buprenorphine for the first time in the study period following the intervention. While there is no “baseline” rate of readiness for buprenorphine administration among EM clinicians overall, our rate of one-third of EM clinicians administering buprenorphine suggests an increase from the 20.9% ED clinicians who recently reported high readiness to initiate buprenorphine in another recent study [17]. Additionally, all the participants reported an increased ability to recognize opioid withdrawal, and this was sustained at 90 days. Such an improvement in self-reported clinical comfort is critical to combating the practitioner-level barriers to expanding ED initiation of buprenorphine.

We also showed that utilizing text-delivered surveys to serially assess knowledge improvements and perceptions about buprenorphine were possible, though participant retention for serial text-based surveys was a challenge. Additional methods such as a financial incentive to report first-time buprenorphine administration and SMS-delivered clinical pearls and social norming demonstrated no significant additional benefit to the educational intervention alone for rates of first-time administration, though our study was not powered to detect a difference for this outcome. This educational intervention was modest, requiring only 30 min of conference time. Content covered could be delivered by any clinician with experience administering buprenorphine and could easily be converted to an online format (see Appendix).

Of note, a significant portion of our study participants reported that they did not encounter an eligible patient to whom they could administer buprenorphine. This was an unexpected yet important result. Previous studies have demonstrated the efficacy of behavioral economics-based interventions on shaping clinician behavior, including for opioid and antibiotic stewardship [25, 26]. While institutions develop interventions to nudge clinician behavior to improve access to buprenorphine for ED patients, a robust understanding of how often patients with OUD present to the ED with opioid withdrawal and/or seeking treatment initiation is critical to developing realistic, feasible, and clinically meaningful outcome targets [14, 23]. Training providers to recognize patients who might have opioid use disorder, even though that might not be the primary reason for their visit, is also important as previous work has demonstrated many patients who receive buprenorphine in the ED do not present with a chief complaint of opioid withdrawal [27]. Furthermore, given the predominance of fentanyl in the opioid supply since the conception of our study, updating buprenorphine induction protocols to minimize the risk of precipitated withdrawal is critical.

ED treatment of opioid use disorder is an opportunity reflective of the expertise of EM clinicians in recognizing time-sensitive conditions and initiating evidence-based treatment with minimal additional training. On April 28, 2021, the United States Department of Health and Human Services put into effect guidelines that allow some practitioners to forgo the 8-h training course when applying for an X-waiver. While the removal of this regulatory burden is a welcome policy change, experts in the field of addiction medicine have proposed the need for focused and specialty-specific training on OUD and buprenorphine [28, 29]. The comfort of providers in initiating buprenorphine varies according to their years in practice and practice setting, with practitioners with more years in practice and those in non-academic settings feeling less comfortable [18]. Our intervention represents one model by which to address this need for focused and brief training among ED clinicians to increase their familiarity with buprenorphine administration independent of the necessity for waiver training. As demonstrated by a recent analysis of calls to the California Poison Control System’s OUD hotline, once practitioners incorporate buprenorphine prescribing to their clinical practice, additional support may be needed for complicated buprenorphine starts, such as among special populations or patients with polysubstance use [30]. As demonstrated by our results, modest incentives and motivational reminders alone are unlikely to result in sustained practice pattern change regarding administration of buprenorphine. This suggests that there is a need to address larger institutional and health-system level barriers preventing adoption of this practice, which may include local ED culture around OUD treatment, availability of outpatient follow-up, and social and health system navigation support from social workers or peer recovery specialists. Furthermore, our results showing the only sustained impact of our intervention was the ability to recognize opioid withdrawal suggests that concerted efforts to improve education on recognizing and treating OUD are necessary, and should be routinely incorporated into medical school and residency training.

Our study has notable limitations. First, we did not include a control group without any training to which we could compare the results of our intervention. Additionally, we relied on self-reported data on buprenorphine administration rather than actual observed changes in administration rates, risking social desirability bias. We did not ascertain when in the 90-day period, buprenorphine was administered or additional demographic or training details of the providers. Because this was a provider-focused intervention, we did not collect patient-level demographics. Given the pre-post nature of our study design, we are unable to attribute clinician behavior changes to our intervention alone, as we cannot account for secular trends. We did not study a comprehensive opioid use disorder curriculum but focused on patients presenting with opioid withdrawal and buprenorphine treatment. The 30-minute curriculum was brief and conducted by a single presenter, which may limit the reproducibility. Additional studies are needed to improve education on prevention, stigma and outpatient management of opioid use disorder, and assessments of necessary knowledge of buprenorphine should be tested and validated. While we included content on “the 72-hour rule” in our didactic intervention, we did not assess if our participants were already aware of this important policy that facilitates ED-administration of buprenorphine without an X-waiver. Additionally, despite a financial incentive, the completion rate of all three surveys was only 59%. While the literature is scarce on text-based surveys, previous studies have demonstrated that physician survey response rates are lower than the general population, can be improved with financial incentives, and that response rates decrease with additional surveys [31,32,33,34]. Because the enhanced group was offered an incentive to report buprenorphine administration, it is possible that financial inducement affected administration in this arm. However, when the participants were asked what influenced their decision to administer buprenorphine, no participant reported the financial incentive in the top three factors affecting their decision. In addition, we did not ascertain from the participants if they encountered OUD patients who were not yet in opioid withdrawal in the ED, and thus clinically ineligible for buprenorphine administration, which is a common clinical scenario. The patients who use fentanyl, in particular, are at risk for precipitated withdrawal, especially when they present with mild withdrawal symptoms [35]. At the time of our didactic, we used a COWs score of “8” to signal mild withdrawal in which buprenorphine could be used, which was consistent with other national protocols [36]. However, recent clinical experience during the rise of fentanyl suggests that a higher COWS score (“13”) is safer to prevent precipitated withdrawal. We did not include home inductions in our study, since that requires having a DATA 2000 waiver to prescribe buprenorphine, although it is a valuable practice to reach patients who are not in withdrawal while in the ED. Although the platform we used to send the messages provided confirmation that the carrier received the messages, we are unable to know if the recipient read the messages. Lastly, this pilot study was not powered to find differences as small as those seen in administration rates.

Conclusion

This intervention targeted to EM clinicians at all levels of clinical practice improved clinical knowledge of and attitudes towards ED administration of buprenorphine only transiently. It did, however, result in a sustained perception of ability to recognize opioid withdrawal. Our results do not suggest that the utilization of behavioral economics-grounded principles of social norming and gain-framed incentivization confers additional benefit to the educational intervention alone in promoting sustained change in clinical knowledge. In order to further expand evidence-based ED treatment of OUD, focused initiatives that improve clinician competence with buprenorphine should be explored. Additional studies to understand effective strategies beyond individual provider-level barriers that will promote ED administration of buprenorphine are warranted.

References

Ochalek TA, Cumpston KL, Wills BK, Gal TS, Moeller FG. Nonfatal Opioid Overdoses at an Urban Emergency Department During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA. 2020;324(16):1673–1674. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.17477

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Increase in fatal drug overdoses across the United States driven by synthetic opioids before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/2020/han00438.asp. Accessed 10 January 2021.

Soares WE 3rd, Melnick ER, Nath B, D'Onofrio G, Paek H, Skains RM, Walter LA, Casey MF, Napoli A, Hoppe JA, Jeffery MM. Emergency Department Visits for Nonfatal Opioid Overdose During the COVID-19 Pandemic Across Six US Health Care Systems. Ann Emerg Med. 2022;79(2):158–167.

Weiner SG, Baker O, Bernson D, Schuur JD. One-year mortality of patients after emergency department treatment for nonfatal opioid overdose. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;75(1):13–7.

Kakko J, Alho H, Baldacchino A, Molina R, Nava FA, Shaya G. Craving in Opioid Use Disorder: From Neurobiology to Clinical Practice. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:592.

Mahmoud S, Anderson E, Vosooghi A, Herring AA. Treatment of opioid and alcohol withdrawal in a cohort of emergency department patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;43:17–20.

Monico LB, Oros M, Smith S, Mitchell SG, Gryczynski J, Schwartz R. One million screened: scaling up SBIRT and buprenorphine treatment in hospital emergency departments across Maryland. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(7):1466–9.

Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017;357:j1550.

Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Feb 6;(2):CD002207. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub4.

Huhn AS, Dunn KE. Why aren’t physicians prescribing more buprenorphine? J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;78:1–7.

Louie DL, Assefa MT, McGovern MP. Attitudes of primary care physicians toward prescribing buprenorphine: a narrative review. BMC Fam Pract. 2019;20(1):157.

Hutchinson E, Catlin M, Andrilla CH, Baldwin LM, Rosenblatt RA. Barriers to primary care physicians prescribing buprenorphine. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(2):128–33.

Im DD, Chary A, Condella AL, et al. Emergency department clinicians’ attitudes toward opioid use disorder and emergency department-initiated buprenorphine treatment: a mixed-methods study. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(2):261–71.

Foster SD, Lee K, Edwards C, et al. Providing incentive for emergency physician X-waiver training: an evaluation of program success and postintervention buprenorphine prescribing. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;76(2):206–14.

D’Onofrio G, O’Connor PG, Pantalon MV, et al. Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313(16):1636–44.

Lowenstein M, Kilaru A, Perrone J, et al. Barriers and facilitators for emergency department initiation of buprenorphine: a physician survey. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(9):1787–90.

Hawk KF, D’Onofrio G, Chawarski MC, et al. Barriers and facilitators to clinician readiness to provide emergency department–initiated buprenorphine. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(5):e204561–e204561.

Zuckerman M, Kelly T, Heard K, Zosel A, Marlin M, Hoppe J. Physician attitudes on buprenorphine induction in the emergency department: results from a multistate survey. Clin Toxicol. 2020;1–7.

Rhee TG, D’Onofrio G, Fiellin DA. Trends in the use of buprenorphine in US emergency departments, 2002–2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2021209–e2021209.

Title 21, Code of federal regulations, part 1306.07(b).

Wiegand TJ. The new kid on the block—incorporating buprenorphine into a medical toxicology practice. J Med Toxicol. 2016;12(1):64–70.

Levels of racism. a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(8):1212–5.

Martin A, Kunzler N, Nakagawa J, et al. Get waivered: a resident-driven campaign to address the opioid overdose crisis. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;74(5):691–6.

Saitz R, Friedmann PD, Sullivan LM, et al. Professional satisfaction experienced when caring for substance-abusing patients: faculty and resident physician perspectives. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(5):373–6.

Gong CL, Zangwill KM, Hay JW, Meeker D, Doctor JN. Behavioral economics interventions to improve outpatient antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory infections: a cost-effectiveness analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(6):846–54.

Delgado MK, Shofer FS, Patel MS, et al. Association between electronic medical record implementation of default opioid prescription quantities and prescribing behavior in two emergency departments. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(4):409–11.

LeSaint KT, Klapthor B, Wang RC, Geier C. Buprenorphine for opioid use disorder in the emergency department: a retrospective chart review. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21(5):1175–81.

Weimer MB, Tetrault JM, Fiellin DA. Patients with opioid use disorder deserve trained providers. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(12):931–2.

Diamond D. Biden kills Trump plan on opioid-treatment prescriptions. The Washington Post. Jan. 27, 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com. Accessed 1 February 2021.

LeSaint KT, Ho RY, Heard SE, Smollin CG. California poison control system implementation of a novel hotline to treat patients with opioid use disorder. J Med Toxicol. 2021;17(2):190–6.

Cook DA, Wittich CM, Daniels WL, West CP, Harris AM, Beebe TJ. Incentive and reminder strategies to improve response rate for internet-based physician surveys: a randomized experiment. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(9):e244.

Flanigan T, McFarlane E, Cook S. Conducting Survey Research among Physicians and Other Medical Professionals—A Review of Current Literature. In: Proceedings of the Survey Research Methods Section. American Statistical Association; 2008. p. 4136–47.

Cunningham CT, Quan H, Hemmelgarn B, et al. Exploring physician specialist response rates to web-based surveys. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15(1):32.

Brtnikova M, Crane LA, Allison MA, Hurley LP, Beaty BL, Kempe A. A method for achieving high response rates in national surveys of U.S. primary care physicians. PLOS ONE. 2018;13(8):e0202755.

Varshneya NB, Thakrar AP, Hobelmann JG, Dunn KE, Huhn AS. Evidence of Buprenorphine-precipitated Withdrawal in Persons Who Use Fentanyl. J Addict Med. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000922.

Guo CZ, D’Onofrio G, Fiellin DA, et al. Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine protocols: a national evaluation. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021;2(6):e12606.

Funding

The Medical Toxicology Foundation (MTF) of the American College of Medical Toxicology (ACMT) received funding from Independence Blue Cross Foundation under the Supporting Treatment and Overdose Prevention (STOP) program to conduct this study. Dr. Utsha Khatri is funded through the Department of Veterans Affairs through the National Clinician Scholars Program. These views do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or of the US government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

UK, KL, and JP conceived the study, designed the trial, supervised the conduct of the trial, and data collection. JP obtained the research funding. JP designed and conducted the training sessions with support from KL and JD. KL managed the technical support, and KL and MP provided the innovation and design expertise. UK, JP, JD, and KL undertook the recruitment and planning of the sessions. FS provided the statistical advice on study design and analyzed the data; UK, KL, and TL managed the data acquisition. UK drafted the manuscript, and all the authors contributed substantially to its revision. UK takes responsibility for the paper as a whole. Trial Registration: clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT03821103.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Additional information

Supervising Editor: Leslie R. Dye, MD

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khatri, U.G., Lee, K., Lin, T. et al. A Brief Educational Intervention to Increase ED Initiation of Buprenorphine for Opioid Use Disorder (OUD). J. Med. Toxicol. 18, 205–213 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13181-022-00890-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13181-022-00890-7